History

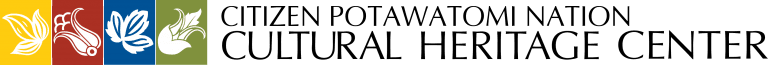

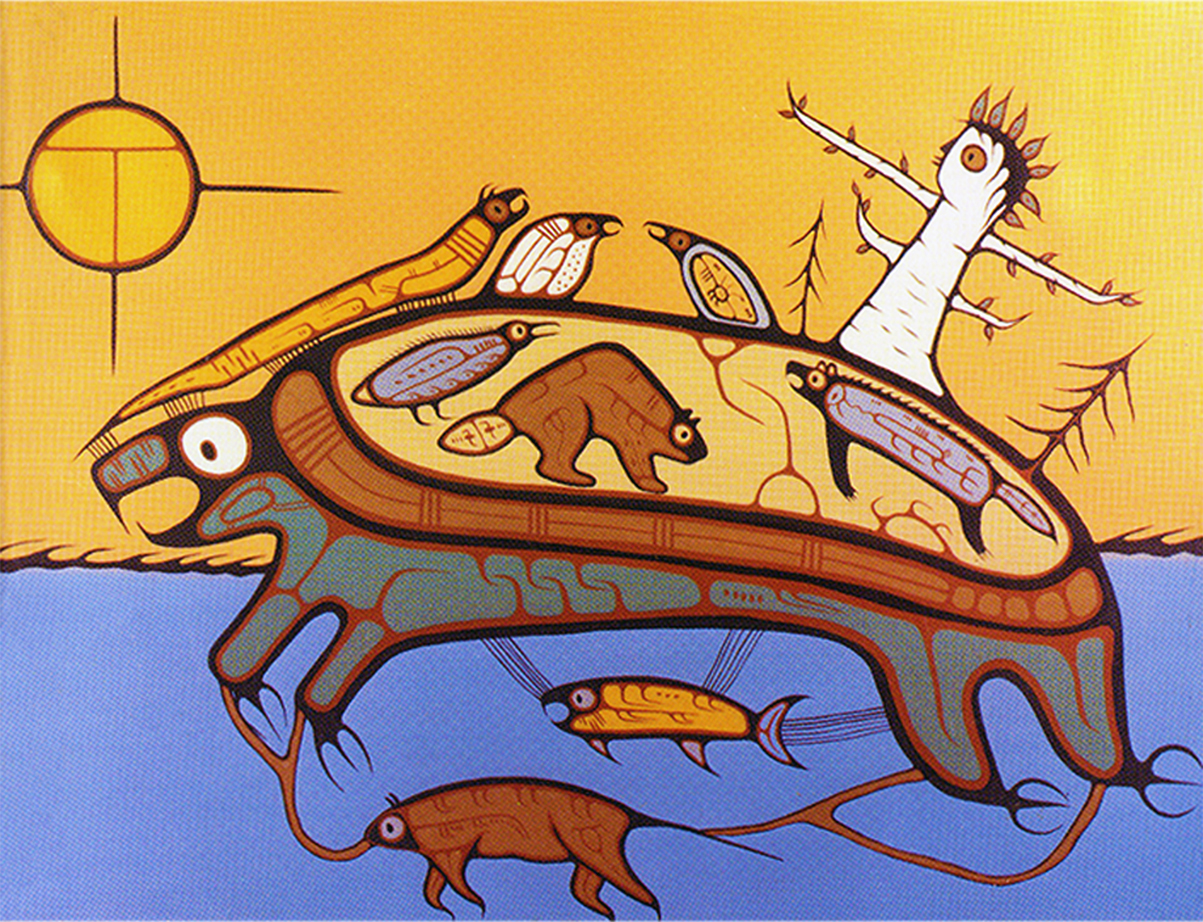

The Flood by Roy Thomas | Courtesy: Charles J. Meyers Great Lakes Indian Art Collection

Origins

Over several millennia, we Neshnabek/Bodewadmi have told the story of our creation and eventual destruction. Believing that the earth and our existence have been manifested in a succession of four worlds, each end is met with great devastation, humility and sacrifice. The story of the Great Flood embodies the compelling and humbling beginning of our fourth and current existence.

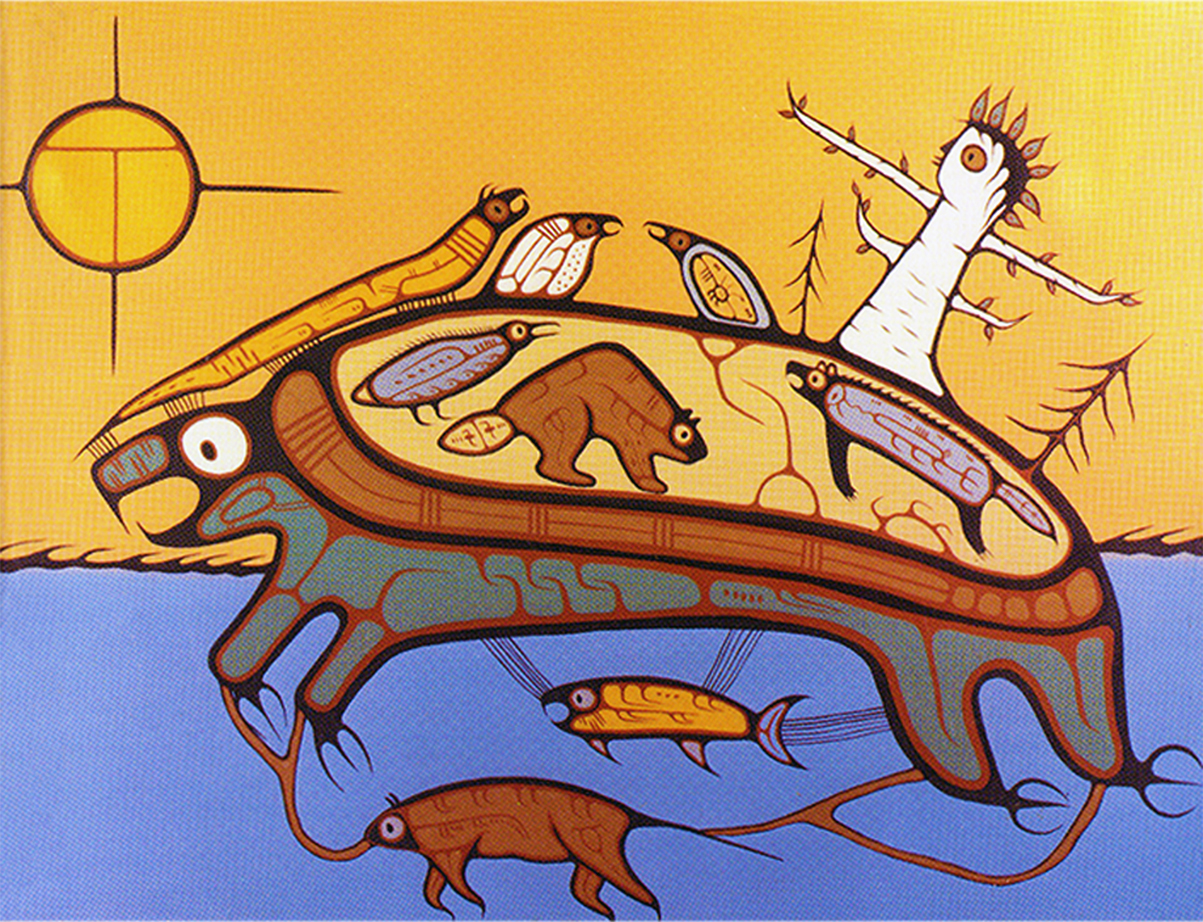

Migration by Norval Morrisseau. ca 1970’s | Courtesy: Royal Ontario Museum

Migration to Great Lakes

Heeding the first prophecy that they must leave their home on the East Coast of North America, the Neshnabek begin a mass migration inland from the Atlantic Coast to the Great Lakes Region. Led by the sacred Megis shell of our Midewewin Lodge, the journey consisted of seven stops, the beginning, and end signified by a turtle-shaped island. Today, these locations are known as Montreal, Niagara Falls, the Detroit River, Manitoulin Island, Sault St. Marie, Spirit and Madeline Islands.

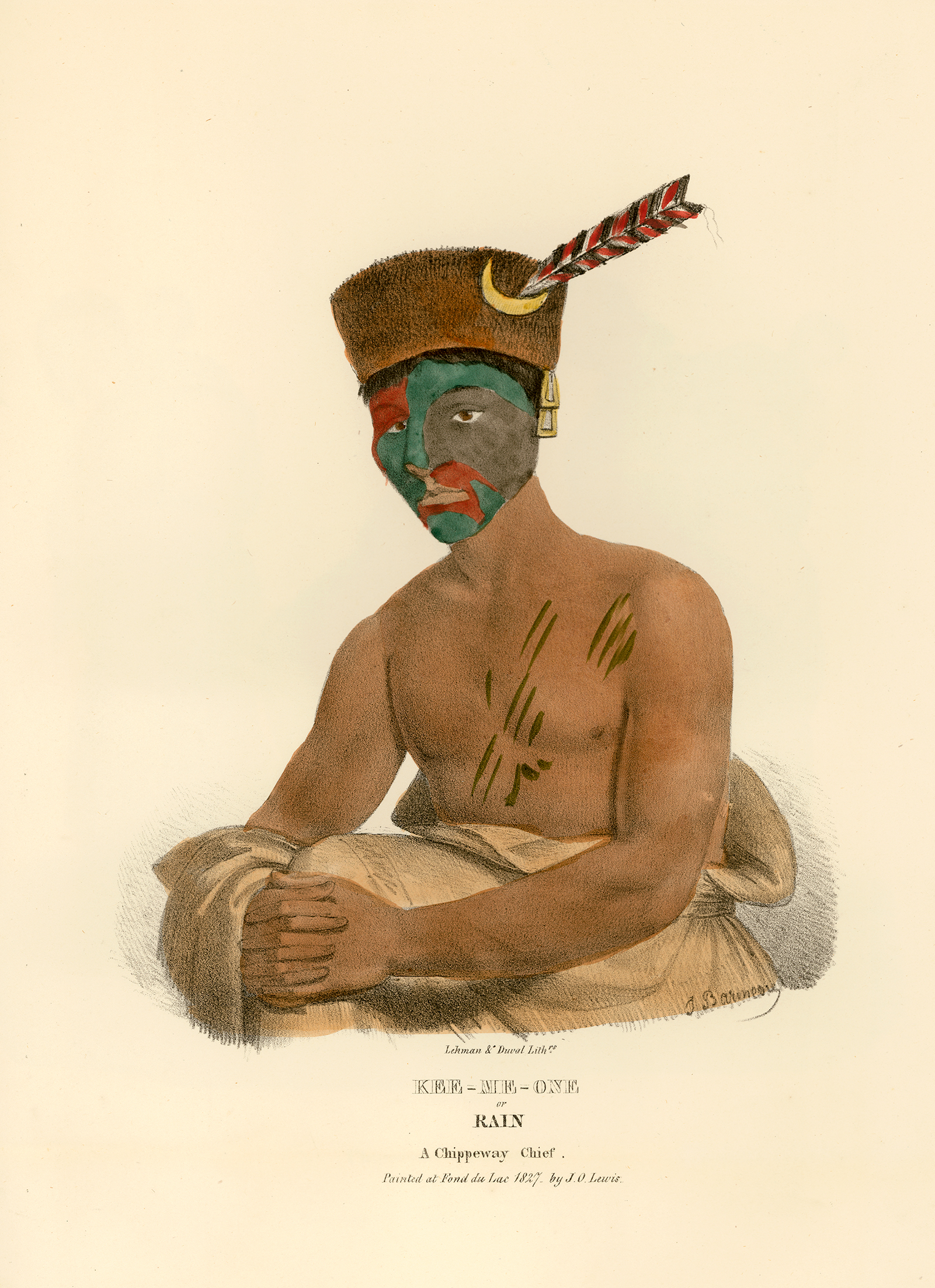

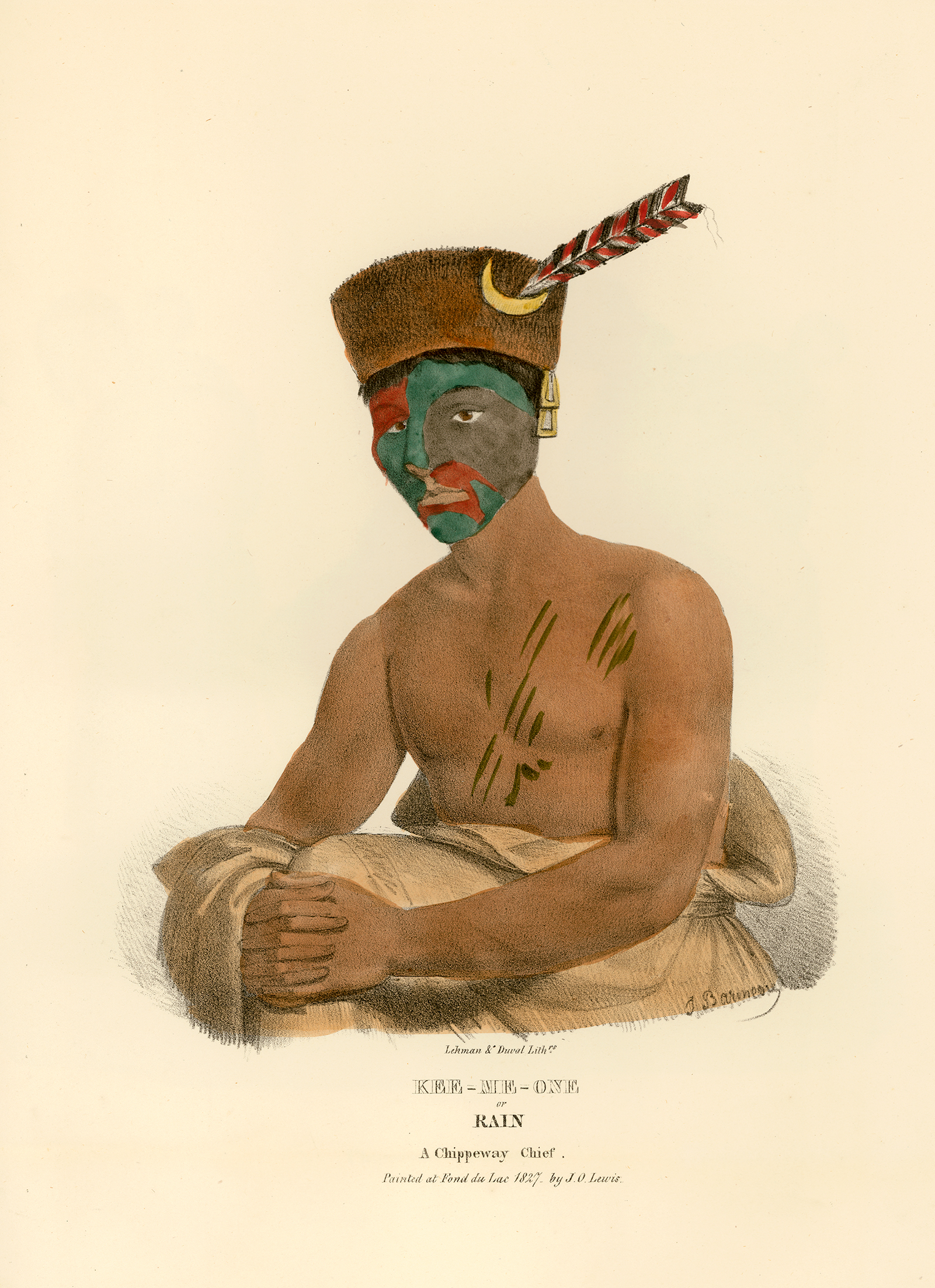

Kee Me One by James Otto Lewis. 1827 | Courtesy: Wisconsin Historical Society

Three Fires Council

It was at Niagara Falls that the Neshnabek disbanded into three distinct tribes. First were the Ojibwe, our Keepers of Medicine, migrating to the north and west of Lake Superior. Next was the Odawa, our Keepers of the Trade, establishing villages to the north of Lakes Superior, Michigan, and Huron. Last to build a fire as one people were the Bodewadmi, known as Keepers of the Fire, migrating south to the coasts of Lake Michigan.

Learn More

The Traders Have Come to Town by Robert Griffing. 2009 | Courtesy: Lord Nelson's Gallery

Establishment of Fur Trade and French Alliance

Early European contact brought fur trade and a short-lived time of prosperity for the Potawatomi people. By 1679, Potawatomi had helped develop fur trading in Wisconsin, and trading relationships with the French and other Europeans led to intermarriage between the two cultures.

Learn More![The Shooting of General Braddock at Fort Duquesne [Pittsburgh] by Edwin Willard Deming. 1755](https://www.potawatomiheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/history5.png)

The Shooting of General Braddock at Fort Duquesne [Pittsburgh] by Edwin Willard Deming. 1755 |

Colonial & Intertribal Wars

From 1628 to 1815, the Potawatomi participated in nine major conflicts. These included the Beaver Wars, the Fox Wars, the French and Indian War, Pontiac’s War, the American Revolutionary War, the Northwest Indian Wars, the Osage War, the Battle of Tippecanoe, and the War of 1812.

Council of Kee Wau Nay by George Winter. 1837 | Courtesy: Glenn A. Black Laboratory of Archaeology and Trustees of Indiana University

Removal from Ancestral Homelands

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 forced thousands of Native Americans to walk from their homes in the Great Lakes and east coast regions to Indian Territory. On the morning of Sept. 4, 1838, a band of 859 Potawatomi, with their leaders shackled and restrained in the back of a wagon, set out on a forced march from their homeland in northern Indiana for a small reserve in present-day Kansas. The journey was a 660-mile trek for which the Potawatomi were not prepared and through terrain to which they were not accustomed. In the end, more than 40 people died during what the Potawatomi came to call the Trail of Death.

Learn More

Pisehedwin, a Potawatomi, and others in front of his Kansas farm home. 1877 | Courtesy: United States National Archives and Records Administration

Treaty of 1861 - Landownership and Citizenship

On Nov. 15, 1861, eight designated “chiefs” and more than 70 other members of the Potawatomi Nation met with federal agents to sign a treaty that initiated the process for acquiring fee-simple land allotments and U.S. citizenship for almost two-thirds of its members. This group, which became known as the Citizen Potawatomi, was among the first tribes to enter into a treaty agreement that included both conditions. The decade that followed brought both successes and great challenges as the Citizen Potawatomi struggled to navigate their evolving status as Native Americans, U.S. citizens, landowners, and dispossessed people.

Learn More

Plat of Pot tawatomie Indian Reservation. 1873 |

Moving to Indian Territory

The provisions for Citizen Potawatomi’s move to Indian Territory were stipulated in a treaty signed on February 27, 1867. In 1869, a party of Citizen Potawatomi traveled to Indian Territory and selected a tract of land that became the site of the Citizen Potawatomi reservation. The earliest families to make the journey to their new reserve arrived in Indian Territory in 1872. Since they paid for the move themselves, these families were among the more affluent Potawatomi families who were able to move from Kansas, including members of the Anderson, Bourbonnais, Melot, Clardy, Pettifer, Bergeron and Toupin families. They were soon followed by more Potawatomi emigrants.

Learn More![Pauline McCoy Lewis and Omar D. Lewis [Vice Chairman]. ca 1920](https://www.potawatomiheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/9b..jpg)

Pauline McCoy Lewis and Omar D. Lewis [Vice Chairman]. ca 1920 |

First Tribal Constitution

The Citizen Potawatomi Nation constitution was adopted in 1938. It was a model constitution provided to many tribes as a result of the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act of 1936. Federal recognition of formal tribal governments was an important component of the shift away from a federal Indian policy of assimilation.

Citizen Potawatomi Nation Family Festival Grand Entry . 1999 |

First CPN Family Reunion Festival

The annual Family Reunion Festival replaced the intertribal powwow in the summer of 1999. The Family Reunion Festival is a celebration of our culture and includes activities such as the Grand Entry, cultural classes, a dance contest, games and General Council. Tribal elections are decided during the Family Reunion Festival.

Groundbreaking at Cultural Heritage Center. 2004 |

Cultural Heritage Center opens

In January of 2006, the CPN Cultural Heritage Center opened its doors. It serves as a space to educate Tribal members and other visitors about the history, culture, and present-day operations of our Tribe through museum exhibits and public programming. In the fall of 2006, the CPN Veterans’ Wall of Honor exhibit was unveiled, displaying photos and military uniforms from Potawatomi veterans.

Learn More

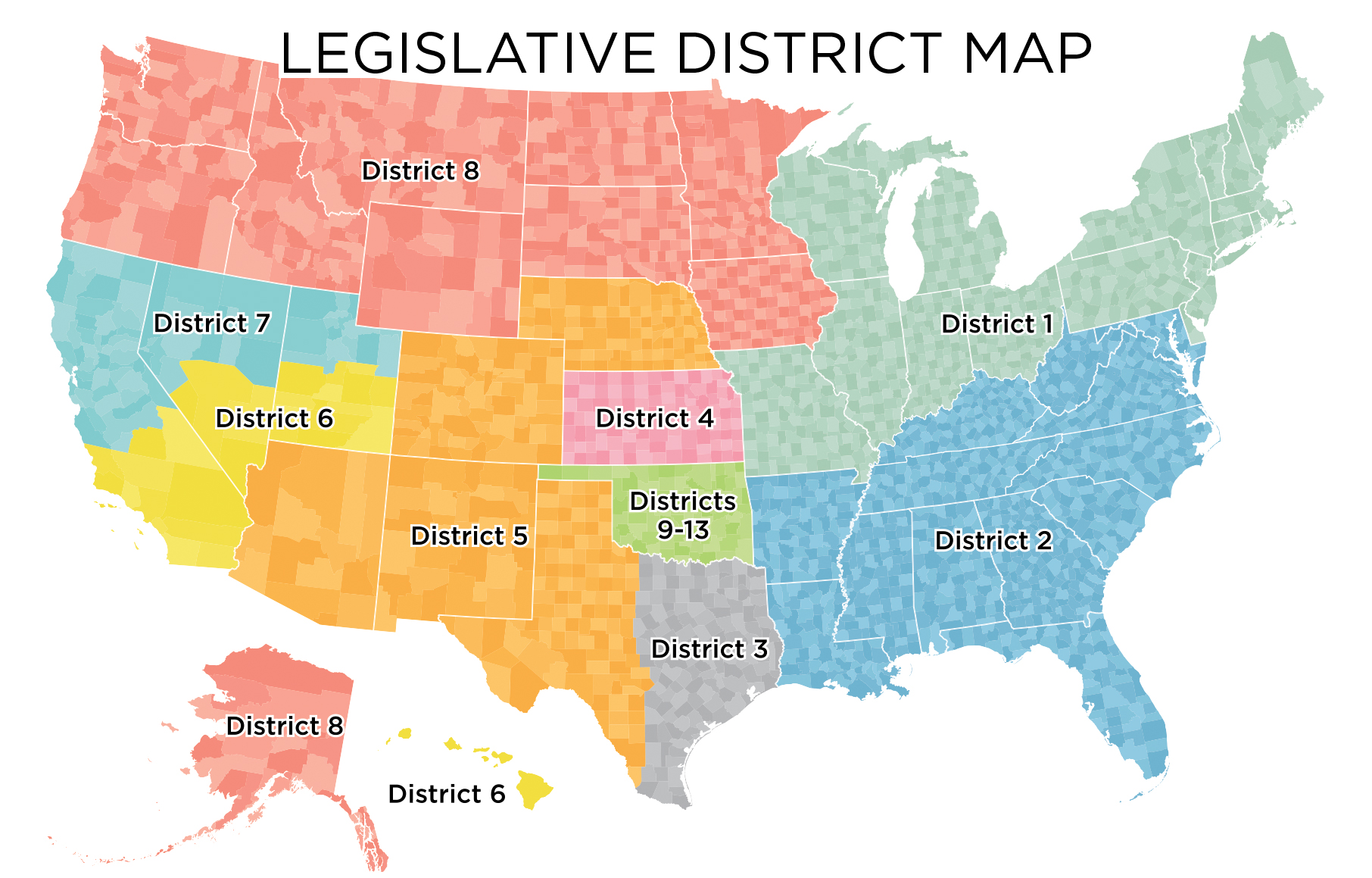

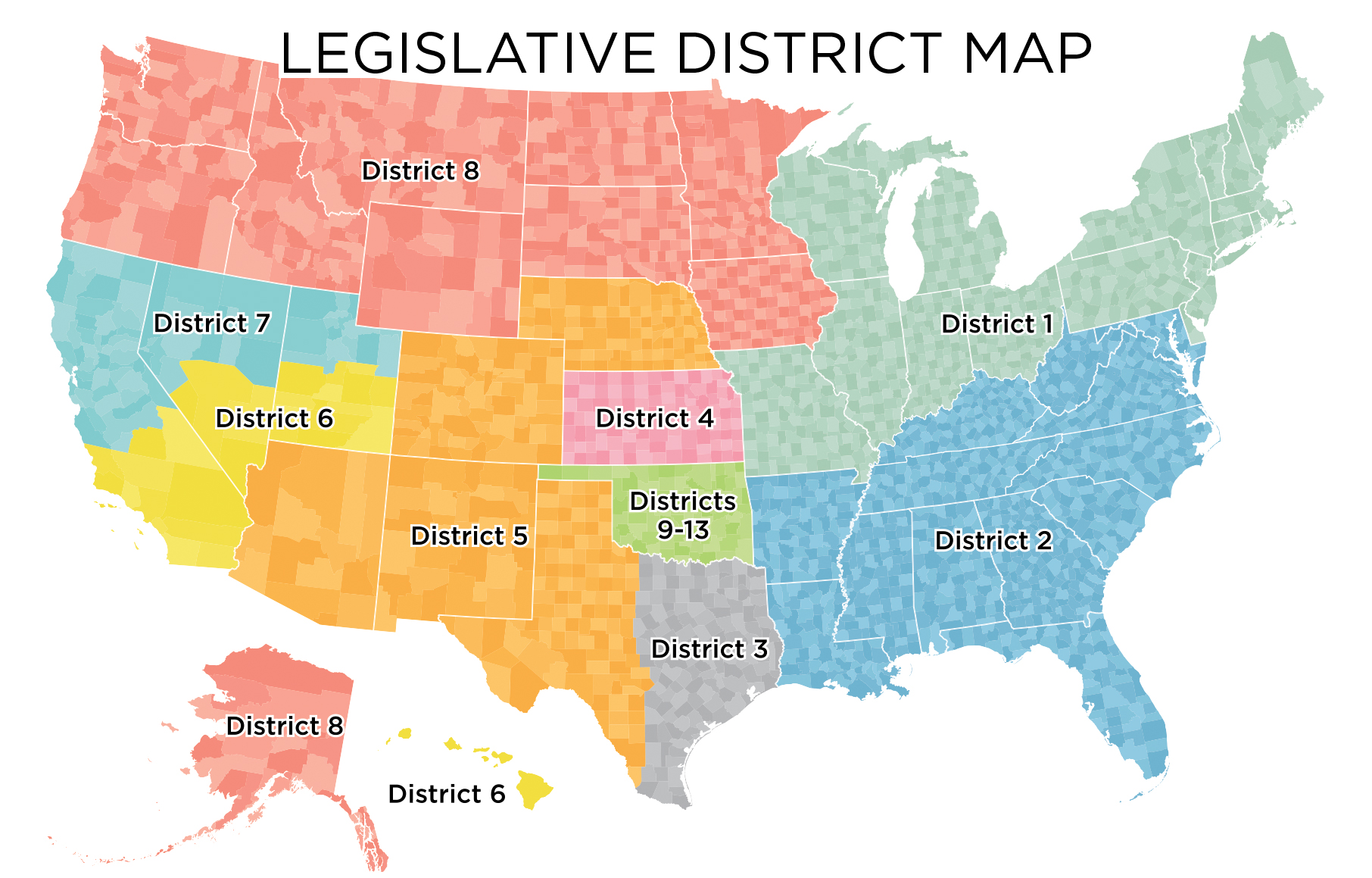

12a.Legislative District Map |

Constitutional reform expands the legislature to provide regional representation

On August 16, 2007, the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ unnecessary oversight of our Tribal government was rejected by voters, and the Citizen Potawatomi Nation overwhelmingly ratified a new constitution. The Citizen Potawatomi Nation refashioned its government structure to properly serve the interests of Tribal members by expanding the legislature to represent members across the United States, prohibiting BIA interference on constitutional amendment adoption, and establishing a clear division of power. Simultaneously, the freedom from federal paternalism represents the strength of tribal sovereignty in our modern age.

Learn More

The Flood by Roy Thomas | Courtesy: Charles J. Meyers Great Lakes Indian Art Collection

Over several millennia, we Neshnabek/Bodewadmi have told the story of our creation and eventual destruction. Believing that the earth and our existence have been manifested in a succession of four worlds, each end is met with great devastation, humility and sacrifice. The story of the Great Flood embodies the compelling and humbling beginning of our fourth and current existence.

Migration by Norval Morrisseau. ca 1970’s | Courtesy: Royal Ontario Museum

Heeding the first prophecy that they must leave their home on the East Coast of North America, the Neshnabek begin a mass migration inland from the Atlantic Coast to the Great Lakes Region. Led by the sacred Megis shell of our Midewewin Lodge, the journey consisted of seven stops, the beginning, and end signified by a turtle-shaped island. Today, these locations are known as Montreal, Niagara Falls, the Detroit River, Manitoulin Island, Sault St. Marie, Spirit and Madeline Islands.

Kee Me One by James Otto Lewis. 1827 | Courtesy: Wisconsin Historical Society

It was at Niagara Falls that the Neshnabek disbanded into three distinct tribes. First were the Ojibwe, our Keepers of Medicine, migrating to the north and west of Lake Superior. Next was the Odawa, our Keepers of the Trade, establishing villages to the north of Lakes Superior, Michigan, and Huron. Last to build a fire as one people were the Bodewadmi, known as Keepers of the Fire, migrating south to the coasts of Lake Michigan.

Learn More

The Traders Have Come to Town by Robert Griffing. 2009 | Courtesy: Lord Nelson's Gallery

Early European contact brought fur trade and a short-lived time of prosperity for the Potawatomi people. By 1679, Potawatomi had helped develop fur trading in Wisconsin, and trading relationships with the French and other Europeans led to intermarriage between the two cultures.

Learn More![The Shooting of General Braddock at Fort Duquesne [Pittsburgh] by Edwin Willard Deming. 1755](https://www.potawatomiheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/history5.png)

The Shooting of General Braddock at Fort Duquesne [Pittsburgh] by Edwin Willard Deming. 1755 |

From 1628 to 1815, the Potawatomi participated in nine major conflicts. These included the Beaver Wars, the Fox Wars, the French and Indian War, Pontiac’s War, the American Revolutionary War, the Northwest Indian Wars, the Osage War, the Battle of Tippecanoe, and the War of 1812.

Council of Kee Wau Nay by George Winter. 1837 | Courtesy: Glenn A. Black Laboratory of Archaeology and Trustees of Indiana University

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 forced thousands of Native Americans to walk from their homes in the Great Lakes and east coast regions to Indian Territory. On the morning of Sept. 4, 1838, a band of 859 Potawatomi, with their leaders shackled and restrained in the back of a wagon, set out on a forced march from their homeland in northern Indiana for a small reserve in present-day Kansas. The journey was a 660-mile trek for which the Potawatomi were not prepared and through terrain to which they were not accustomed. In the end, more than 40 people died during what the Potawatomi came to call the Trail of Death.

Learn More

Pisehedwin, a Potawatomi, and others in front of his Kansas farm home. 1877 | Courtesy: United States National Archives and Records Administration

On Nov. 15, 1861, eight designated “chiefs” and more than 70 other members of the Potawatomi Nation met with federal agents to sign a treaty that initiated the process for acquiring fee-simple land allotments and U.S. citizenship for almost two-thirds of its members. This group, which became known as the Citizen Potawatomi, was among the first tribes to enter into a treaty agreement that included both conditions. The decade that followed brought both successes and great challenges as the Citizen Potawatomi struggled to navigate their evolving status as Native Americans, U.S. citizens, landowners, and dispossessed people.

Learn More

Plat of Pot tawatomie Indian Reservation. 1873 |

The provisions for Citizen Potawatomi’s move to Indian Territory were stipulated in a treaty signed on February 27, 1867. In 1869, a party of Citizen Potawatomi traveled to Indian Territory and selected a tract of land that became the site of the Citizen Potawatomi reservation. The earliest families to make the journey to their new reserve arrived in Indian Territory in 1872. Since they paid for the move themselves, these families were among the more affluent Potawatomi families who were able to move from Kansas, including members of the Anderson, Bourbonnais, Melot, Clardy, Pettifer, Bergeron and Toupin families. They were soon followed by more Potawatomi emigrants.

Learn More![Pauline McCoy Lewis and Omar D. Lewis [Vice Chairman]. ca 1920](https://www.potawatomiheritage.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/9b..jpg)

Pauline McCoy Lewis and Omar D. Lewis [Vice Chairman]. ca 1920 |

The Citizen Potawatomi Nation constitution was adopted in 1938. It was a model constitution provided to many tribes as a result of the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act of 1936. Federal recognition of formal tribal governments was an important component of the shift away from a federal Indian policy of assimilation.

Citizen Potawatomi Nation Family Festival Grand Entry . 1999 |

The annual Family Reunion Festival replaced the intertribal powwow in the summer of 1999. The Family Reunion Festival is a celebration of our culture and includes activities such as the Grand Entry, cultural classes, a dance contest, games and General Council. Tribal elections are decided during the Family Reunion Festival.

Groundbreaking at Cultural Heritage Center. 2004 |

In January of 2006, the CPN Cultural Heritage Center opened its doors. It serves as a space to educate Tribal members and other visitors about the history, culture, and present-day operations of our Tribe through museum exhibits and public programming. In the fall of 2006, the CPN Veterans’ Wall of Honor exhibit was unveiled, displaying photos and military uniforms from Potawatomi veterans.

Learn More

12a.Legislative District Map |

On August 16, 2007, the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ unnecessary oversight of our Tribal government was rejected by voters, and the Citizen Potawatomi Nation overwhelmingly ratified a new constitution. The Citizen Potawatomi Nation refashioned its government structure to properly serve the interests of Tribal members by expanding the legislature to represent members across the United States, prohibiting BIA interference on constitutional amendment adoption, and establishing a clear division of power. Simultaneously, the freedom from federal paternalism represents the strength of tribal sovereignty in our modern age.

Learn More